Foundation Models for Computational Science

Motivation

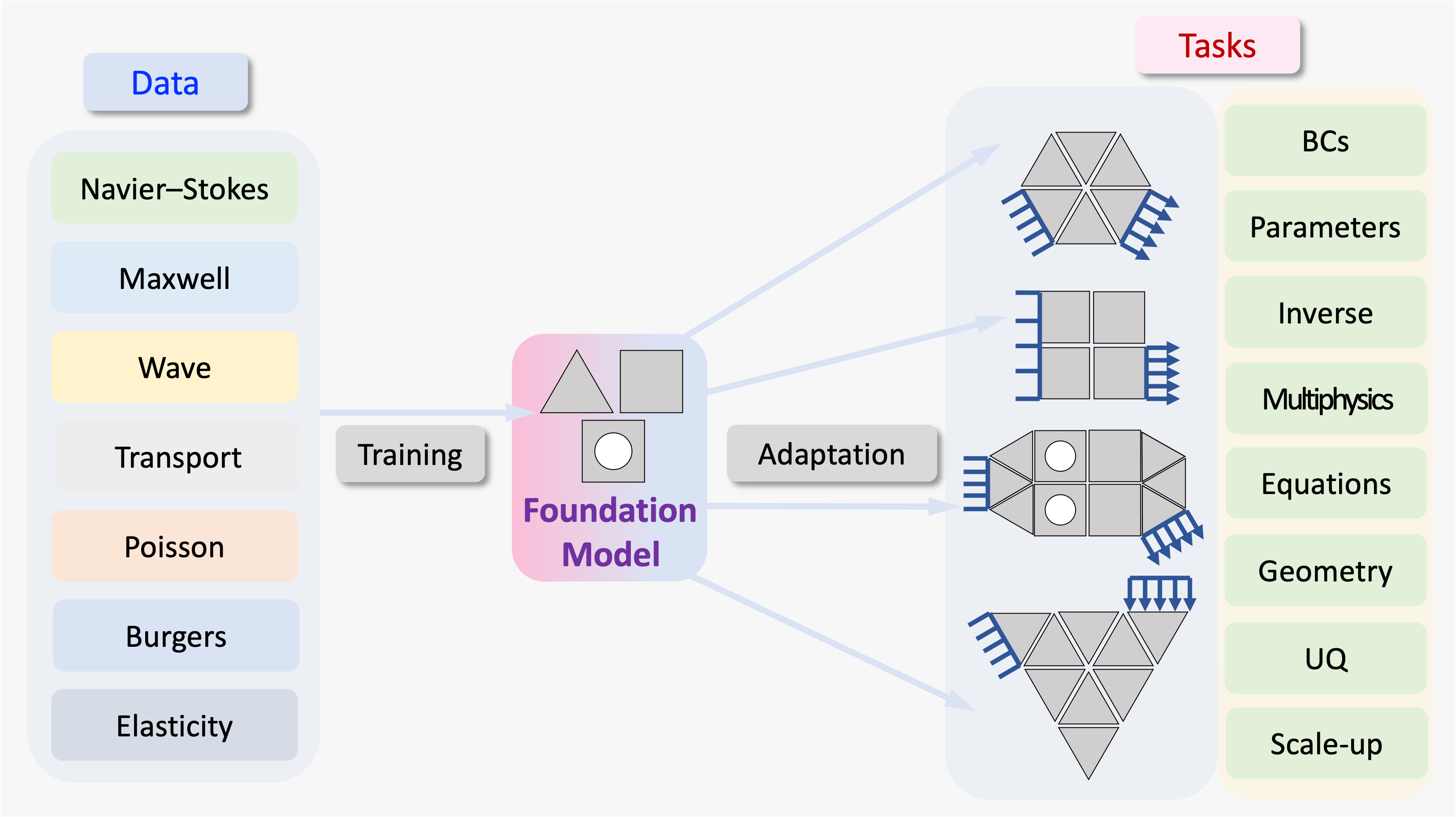

Foundation models have transformed natural language processing and computer vision by enabling reusable, adaptable models that generalize across tasks and domains. Achieving an analogous capability in computational science is far more challenging due to the diversity of governing equations, geometries, physical regimes, and discretizations.

libROM team addresses this challenge through the Data-Driven Finite Element Method (DD-FEM) — a general architectural framework that combines data-driven local modeling with classical finite-element-style global assembly. Importantly, DD-FEM is not a conceptual proposal: it has been realized in multiple production-quality algorithms, each demonstrated through published numerical examples.

What Is a Foundation Model in Computational Science?

In computational science, a foundation model must satisfy requirements beyond those in data-centric ML fields. In particular, it must:

- generalize across geometries, domains, and boundary conditions,

- be reusable without retraining for every new global configuration,

- enforce governing equations and physical constraints explicitly,

- scale to large systems using data from smaller subsystems,

- admit mathematical analysis (stability, error bounds, convergence).

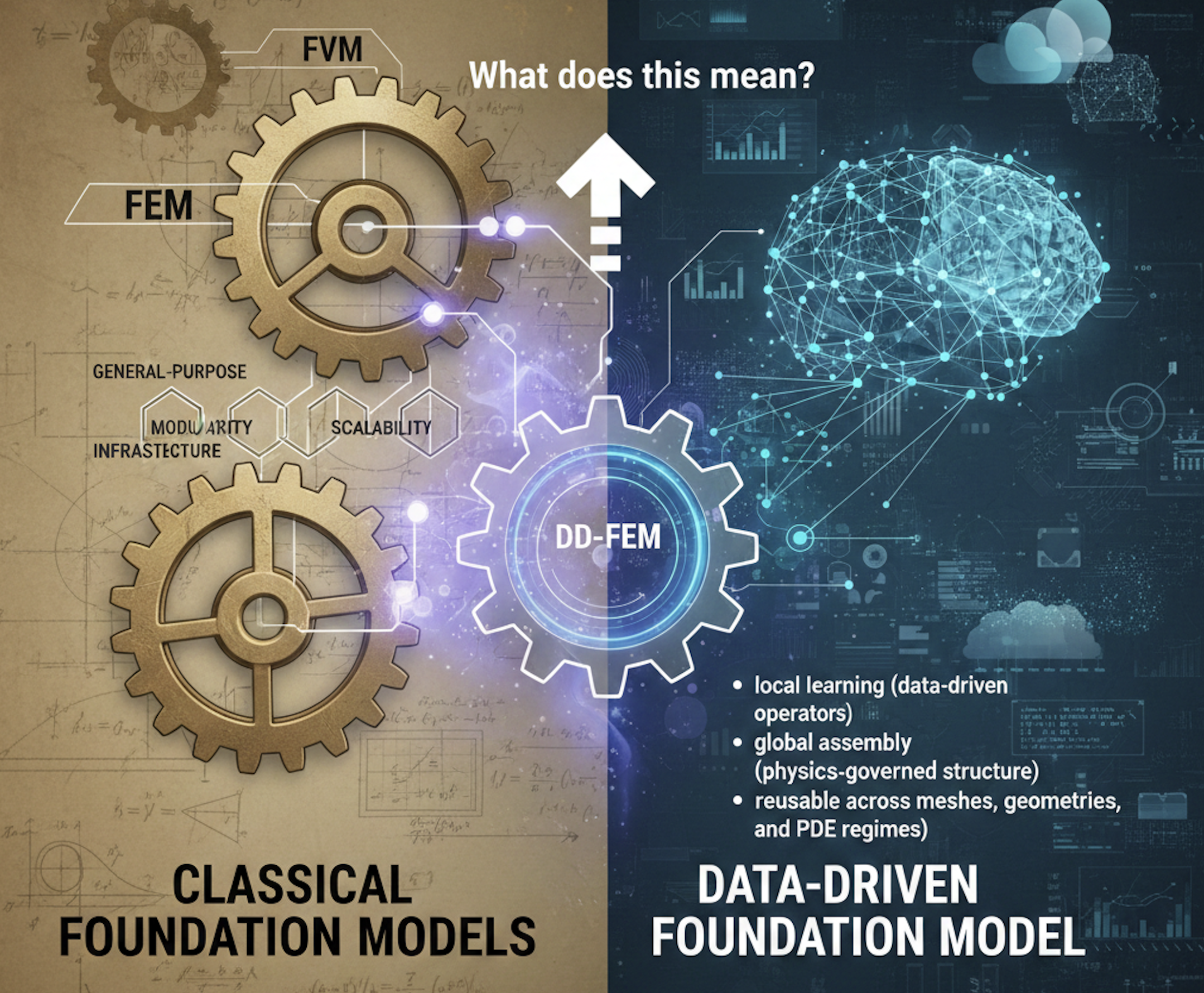

Inspiration from Classical Foundational Methods

Our definition of a foundation model for computational science is intentionally inspired by classical foundation methods that have underpinned scientific computing for decades, most notably the finite element method (FEM) and the finite volume method (FVM).

These methods are considered foundational not because they solve a single problem optimally, but because they provide a general, reusable, and composable framework applicable across a broad range of governing equations, geometries, and physical regimes. FEM and FVM achieve this through:

- local representations that are independent of global problem size,

- systematic assembly into large-scale global systems,

- explicit enforcement of conservation laws and governing equations,

- extensibility across domains without redesigning the core methodology.

In this sense, FEM and FVM already embody many of the characteristics now associated with “foundation models”: generality, reusability, scalability, and scientific rigor.

Our definition of foundation models for computational science builds directly on these principles. Rather than viewing foundation models as purely data-driven artifacts, we frame them as architectural frameworks that integrate learning into the same local-to-global, physics-constrained structure that has made FEM and FVM foundational to scientific computing.

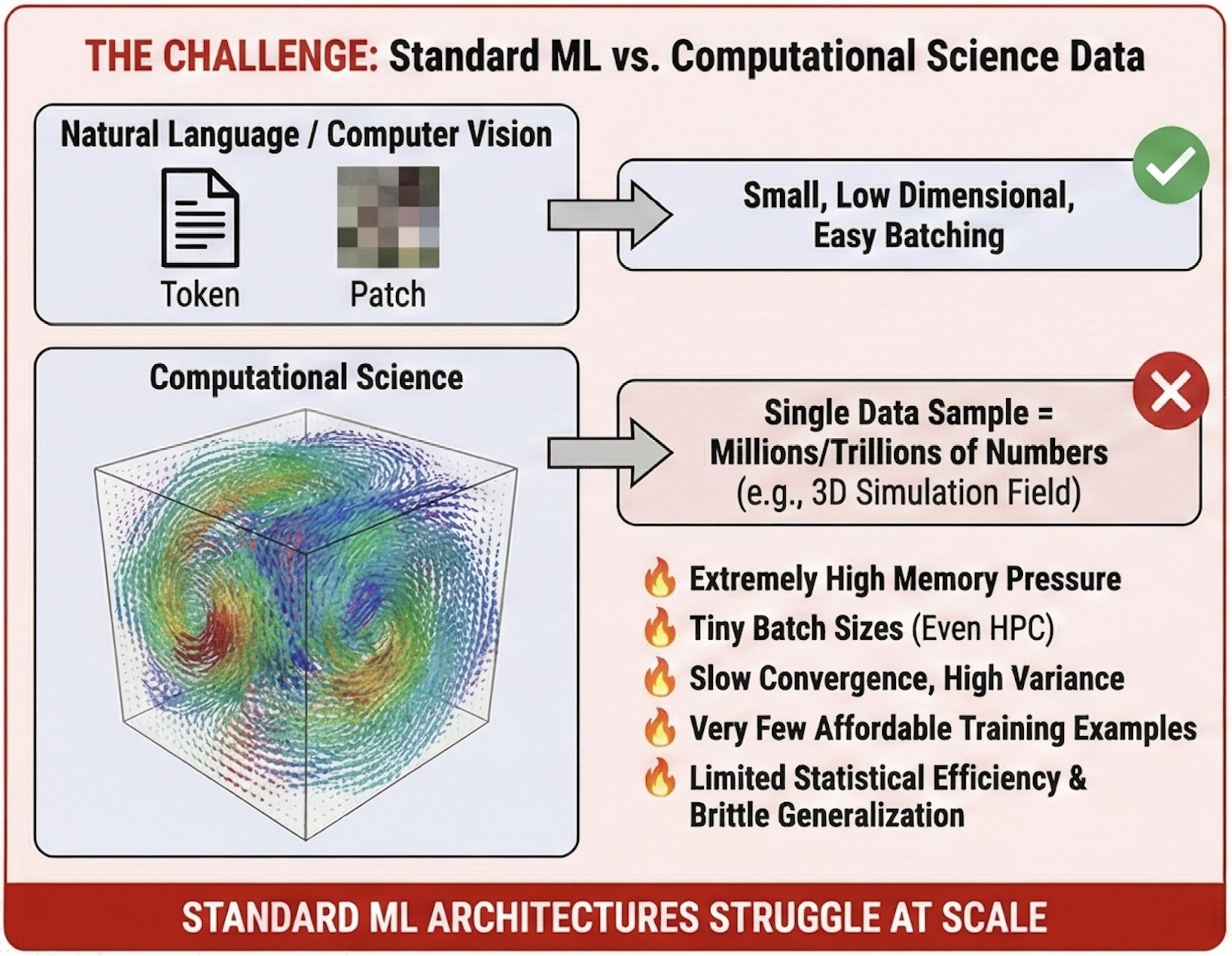

Challenges of Building Foundation Models in Computational Science

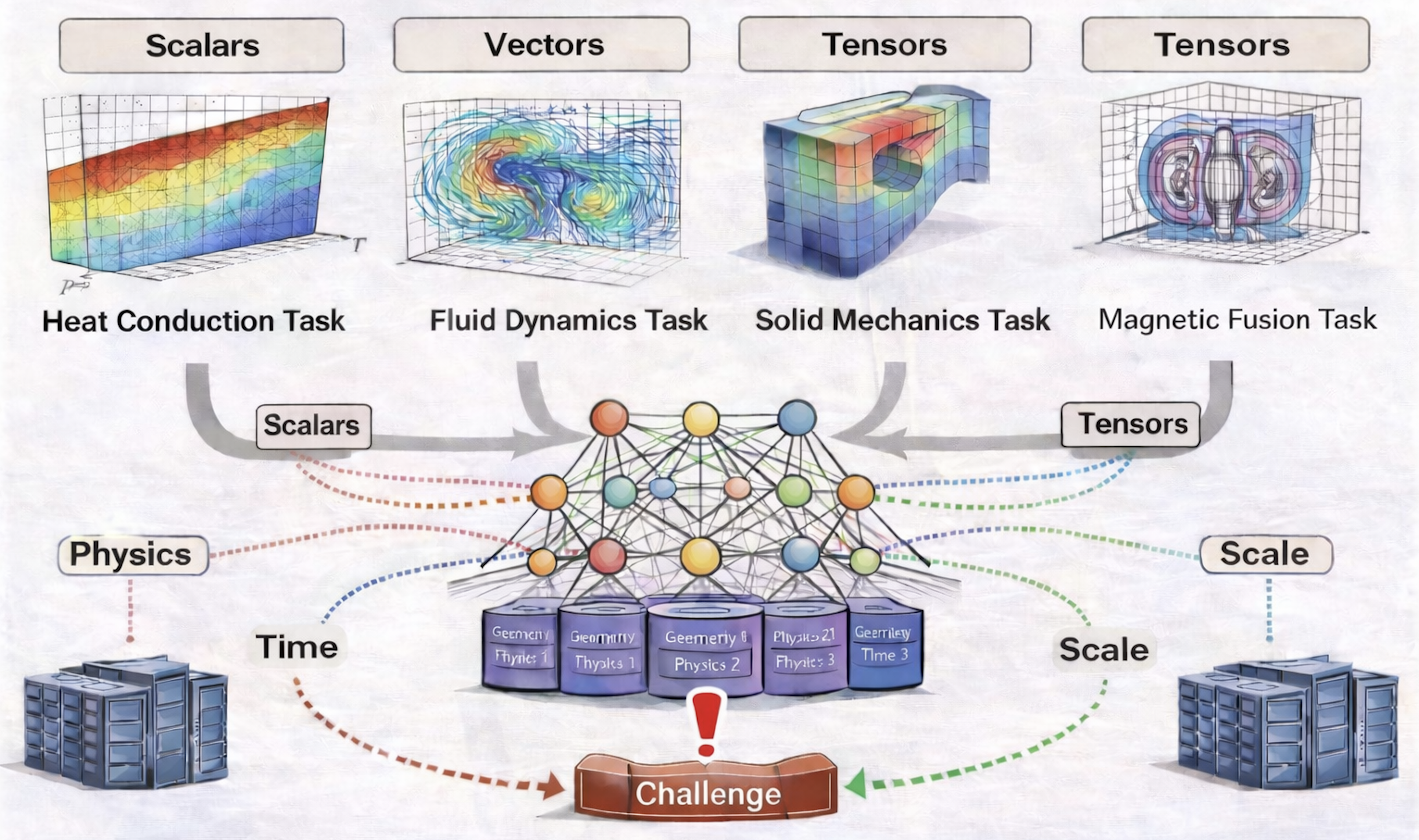

Developing foundatin models in computational science is fundamentally harder than in natural language processing or vision. The Defining Foundation Models for Computational Science position paper [1] outlines several structural obstacles that must be addressed before truly general, reusable scientific foundation models can be achieved.

Massive Data Point Size

In NLP or computer vision, individual data points (tokens, image patches) are small and easily batched for training. In contrast, a single high-fidelity scientific simulation snapshot can contain millions to trillions of degrees of freedom. This:

- creates huge memory and compute burdens,

- limits batch sizes,

- slows convergence of training, and

- makes overfitting more likely with limited data.

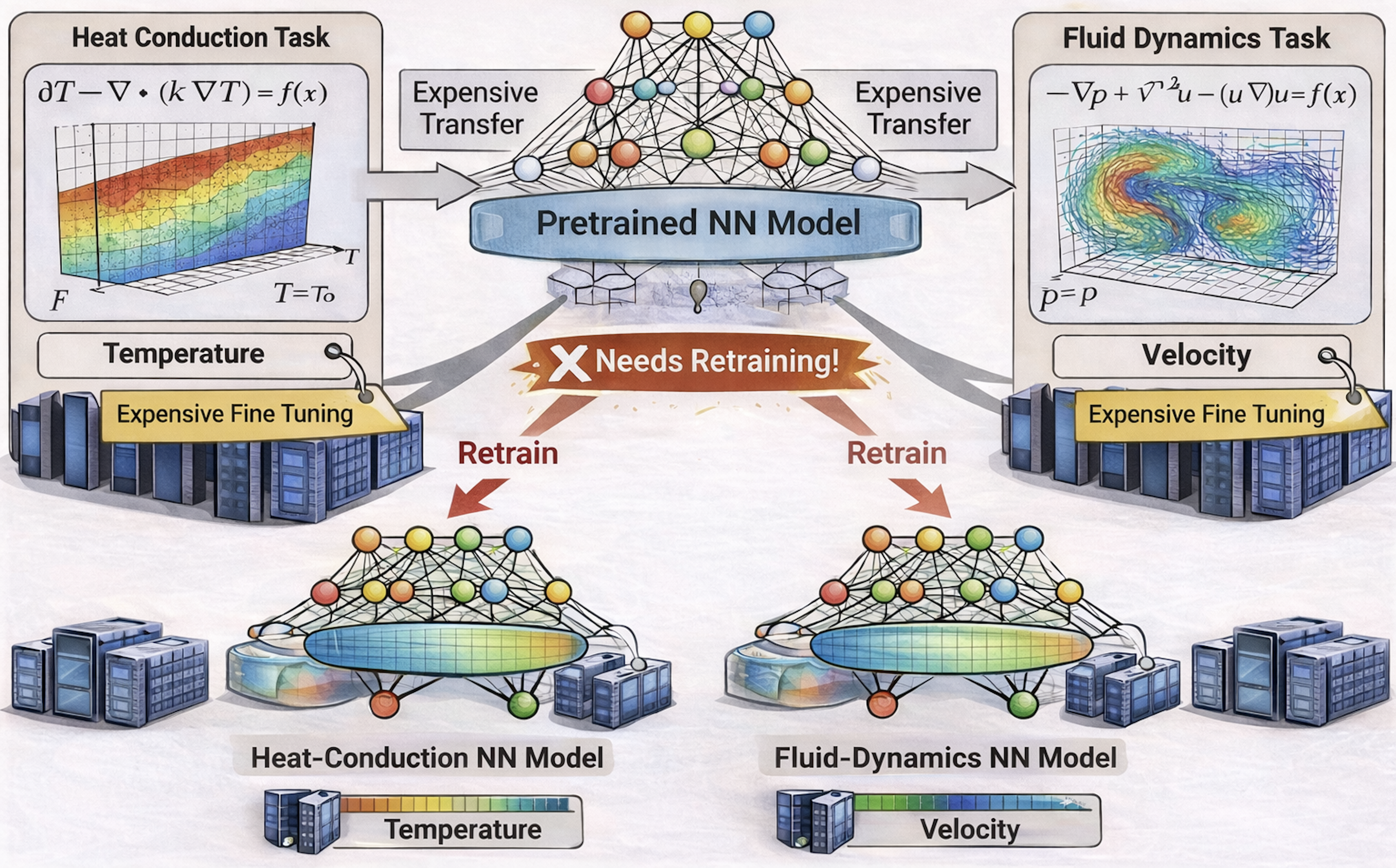

Expensive Fine-Tuning Across Tasks

Foundation models should adapt to new tasks with minimal additional training. In computational science, however, downstream problems frequently differ in PDE type, geometry, mesh resolution, boundary conditions, or time-dependent behavior. Fine-tuning on such distinct tasks can be computationally expensive, undermining reusability and scalability.

Data Heterogeneity

Scientific systems involve a wide range of data types (scalars, vectors, tensors), multi-physics couplings, and time dependencies. Designing a single architecture that meaningfully integrates such heterogeneous data across domains is an open research challenge.

Lack of Standardized Datasets

Unlike NLP and vision, large standardized datasets covering multiple physics domains do not exist. The absence of shared, high-quality datasets hampers large-scale pretraining and makes it hard to benchmark and compare scientific foundation models.

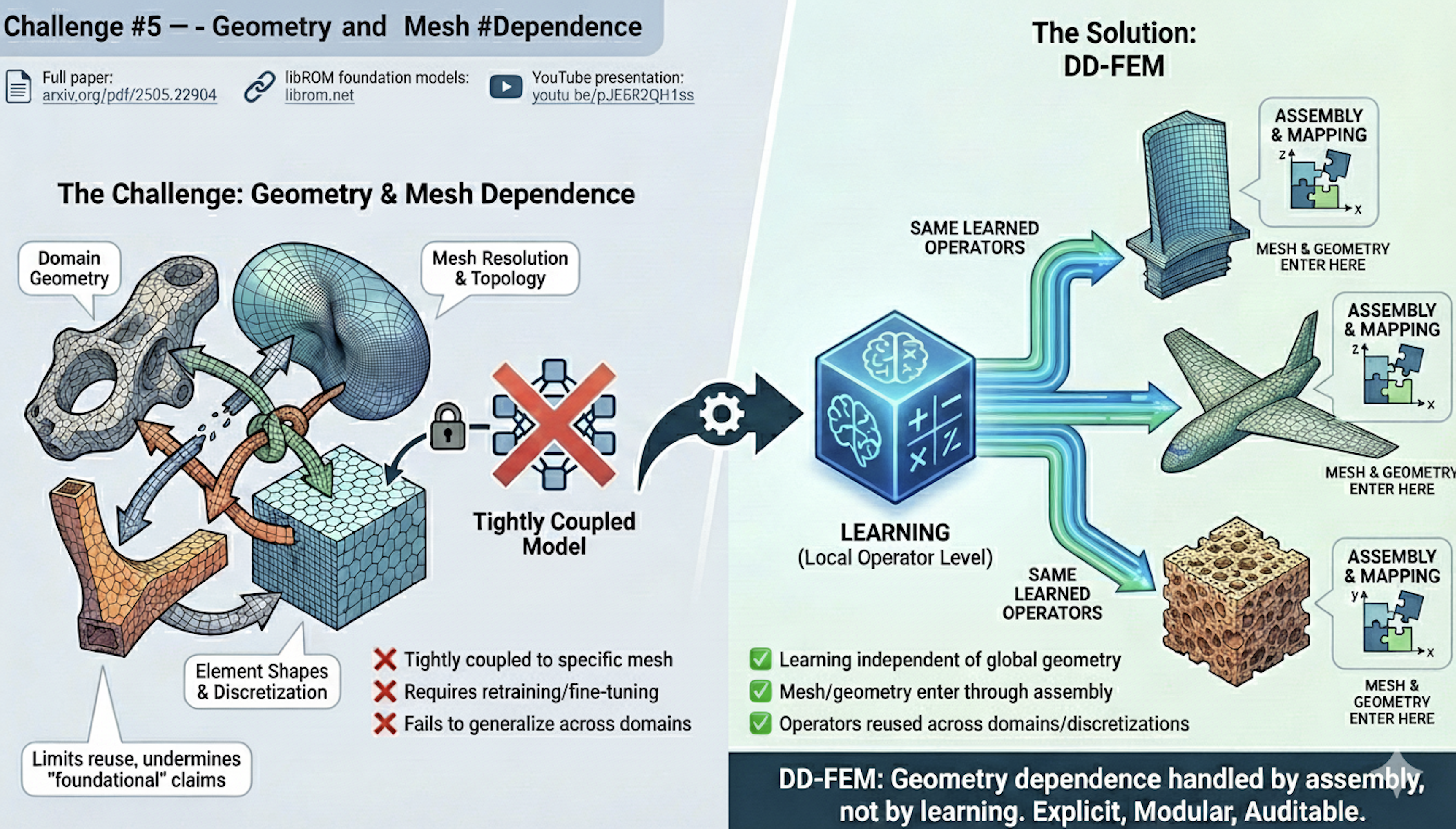

Mesh and Geometry Dependence

Scientific simulations depend intrinsically on the computational mesh and domain geometry. Changes in mesh resolution, element type, topology, or geometry can invalidate naive generalization because many learned models are tied to a fixed discretization.

Crucially, this dependence also forces expensive fine-tuning: as geometry or mesh changes, reuse of a monolithic model is often impossible, making large-scale retraining (or heavy fine-tuning) unavoidable. This breaks scalability and undermines the reusability expected of foundation models.

Physics-Informed Constraints

Scientific systems obey conservation laws, symmetries, and boundary conditions. Enforcing these constraints in learned models without degrading generality is a major open problem. Many ML models either ignore physical laws or hard-code specific physics, limiting flexibility.

Trust, Interpretability, and Scientific Validity

For adoption in engineering and science, models must be interpretable, verifiable, and physically consistent. Black-box neural models that violate conservation or produce nonphysical results are difficult to trust in high-stakes applications.

Multiscale and Long-Time Behavior

Real scientific systems often involve multiple spatial and temporal scales (e.g., turbulence, fracture, phase change). Capturing long-time dynamics and multi-scale interactions in a single model — especially without retraining — remains a critical open challenge.

These challenges suggest that foundation models in computational science cannot be constructed as purely data-driven, end-to-end surrogates. Instead, they require an architectural framework that integrates learning with classical numerical structure, supports local training with global reuse, and preserves scientific rigor.

The Data-Driven Finite Element Method (DD-FEM) provides such a framework.

The Data-Driven Finite Element Method (DD-FEM)

Core Principle

DD-FEM replaces classical finite-element shape functions with learned local models trained on component-level data, while retaining:

- Local training on small subdomains or components

- Global assembly via domain decomposition or finite-element-style coupling

- Explicit solution of governing equations

- Reuse of pretrained components across unseen global systems

This mirrors the role of basis functions in FEM, but with learned representations that can capture multiscale, nonlinear, and parameterized physics more efficiently.

Implemented DD-FEM Realizations through libROM open source codes

DD-FEM is a framework, not a single algorithm. libROM contains multiple, independently developed realizations that instantiate this framework in different settings.

1. ScaleUpROM: Projection-Based DD-FEM with DG Assembly

ScaleUpROM is a DD-FEM realization using projection-based reduced order models coupled through discontinuous Galerkin domain decomposition (DG-DD).

Key characteristics: - Local ROMs trained only on small components - Global systems assembled without retraining - Robust spatial extrapolation (“train small, model big”) - Physics-constrained solves at all scales

ScaleUpROM has been demonstrated on Poisson, Stokes, and Navier–Stokes problems, achieving order-of-magnitude speedups with percent-level accuracy.

See also: ScaleUpROM examples.

2. Component-Wise Reduced Order Models for Design and Optimization

Component-wise ROMs represent an early and foundational instantiation of DD-FEM. In these methods, reduced operators are learned on reusable components and assembled to form global systems.

Representative applications include: - Lattice-type structure design optimization - Compliance minimization and stress-constrained topology optimization - Static condensation-based assembly

These methods demonstrate: - reusable offline training across many design instances, - up to 1000× speedup over full FEM, - rigorous error bounds and sensitivity analysis.

See: - Component-wise ROM lattice optimization - Stress-constrained topology optimization with component ROMs

3. DD-LSPG: Nonlinear Algebraic DD-FEM

DD-LSPG extends DD-FEM to nonlinear systems using least-squares Petrov–Galerkin projection at the subdomain level.

Distinctive features: - algebraic (not geometric) domain decomposition, - independent local bases for interior and interfaces, - strong or weak compatibility enforcement, - a priori and a posteriori error bounds.

This realization shows that DD-FEM applies beyond linear PDEs and FEM-style weak forms.

Reference: - Domain-decomposition LSPG ROMs

4. Nonlinear-Manifold DD-FEM (DD-NM-ROM)

DD-FEM also supports nonlinear manifold representations, where local bases are replaced by learned nonlinear maps (e.g., autoencoders).

In DD-NM-ROM: - nonlinear manifolds are trained independently on subdomains, - coupling is enforced through algebraic DD constraints, - training cost scales with component size, not global size, - hyper-reduction enables efficient nonlinear evaluation.

These methods demonstrate: - superior accuracy for problems with slow Kolmogorov n-width decay, - stable extrapolation from small to large domains, - strong theoretical guarantees.

References: - DD nonlinear-manifold ROM with theory and error bounds - Scalable DD-NM-ROM for dynamical systems

Why DD-FEM Qualifies as a Foundation-Model Framework

Across all realizations, DD-FEM exhibits the defining traits of foundation models in computational science:

- Reusability: pretrained components apply across many global systems

- Generalization: extrapolation in domain size, geometry, and configuration

- Scalability: training cost decoupled from global problem size

- Scientific rigor: governing equations enforced explicitly

- Extensibility: linear, nonlinear, projection-based, and manifold-based models

DD-FEM plays the same foundational role for data-driven simulation that FEM plays for classical numerical analysis.

DD-FEM in libROM

libROM open-source codes serve as an open research platform for DD-FEM, supporting:

- component-level training workflows,

- multiple assembly strategies (DG, static condensation, residual minimization),

- linear and nonlinear reduced representations,

- integration with MFEM and large-scale HPC solvers.

Concrete numerical demonstrations are available throughout the Examples and ScaleUpROM pages.

References

[1] Y. Choi et al., Defining Foundation Models for Computational Science: A Call for Clarity and Rigor, arXiv:2505.22904, 2025.

[2] S. McBane and Y. Choi, Component-wise reduced order model lattice-type structure design, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 381 (2021).

[3] S. McBane, Y. Choi, and K. Willcox, Stress-constrained topology optimization of lattice-like structures using component-wise reduced order models, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 400 (2022).

[4] C. Hoang, Y. Choi, and K. Carlberg, Domain-decomposition least-squares Petrov–Galerkin nonlinear model reduction, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 384 (2021).

[5] A. N. Diaz and Y. Choi, A fast and accurate domain decomposition nonlinear manifold reduced order model, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 425 (2024).

[6] S. W. Chung et al., Train small, model big: Scalable physics simulators via reduced order modeling and domain decomposition, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 427 (2024).

[7] S. W. Chung et al., Scaled-up prediction of steady Navier-Stokes equation with component reduced order modeling, arXiv:2410.21534, 2025.